Datafication of education and automated inequaities

Some musings this week on datafication and Fischer Family Trust Data (FFTD).

The Fischer Family Trust describes

its mission as to 'help children achieve their very best’ by ‘providing expert

data and literacy tools to support schools globally in improving pupil outcomes’

(fft.org.uk, 2017) and has developed a data system for pupil performance which

is now used by the majority of schools in England and Wales. The system (known

as FFTD) calculates estimated attainment targets for school children by

analysing the performance data of students from the previous year with the same

prior attainment in their previous nationally benchmarkable Key Stage

assessments (for English secondary school pupils this would be Key Stage 2),

the same gender, and the same month of birth. The analysis generates predictive

targets for pupil attainment at the next nationally benchmarkable Key Stage,

which for English secondary school students would be Key Stage 4 (GCSE).

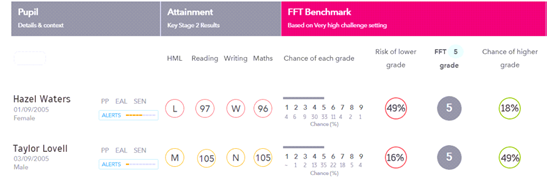

The target looks something like

the examples below, in which, as a result of the application of the three

indicators, both students have been assigned GCSE targets of grade 5.

(fft.org.uk, 2017 – Date Accessed: 31.10.22)

It is important to say that,

typically, school children in England are informed of their target grades and

encouraged to work hard to meet and exceed these. This is for two main reasons.

First, yearly school performance is judged on a value called ‘Progress 8’ which

is calculated by analysing the extent to which a school’s student body exceeds

their expected performance at the end of a Key Stage. A school with a poor Progress

8 score will be automatically inspected by Ofsted, the English school

inspectorate. Second, Ofsted have historically used value added attainment data

as a key factor when making judgements on the effectiveness of a school.

Since 2019, attainment data has

been used more judiciously by school inspectors as an indicator of school

performance, nevertheless, Ofsted still state that schools in which ‘The

attainment and progress of students are consistently low and show little or no

improvement over time, indicating that students are underachieving considerably’

(2019) will be deemed as Inadequate.

I have a number of thoughts in

response to the use of FFTD in schools. First, I think that it is good that

schools are keen to know that their pupils are successful. Comparing their

achievement to that of “similar” peers is a way to do so. I feel uneasy,

however, about the three indicators that are used to determine what constitutes

a “similar” pupil. Prior attainment is little more than a snapshot of

performance at a single moment in time and, although there is plenty of

evidence to support gender and month of birth as strong indicators of academic performance,

the sociology of the selection of just these two demographic indicators needs

deep exploration. A 1991 study by Gordon and Kravertz found a larger gap in

terms of cognitive functioning between left and right handed people than

between males and females, for example. If this is having a greater impact on

attainment than gender, should this be accounted for in FFTD?

We also have an issue when it

comes to the trustworthiness of the data we are giving to our young people, and

the expectations and social pressures that go hand in hand with that. In the

example above, Hazel and Taylor have been generated the same GCSE target grade.

Taylor, however, is much more likely to achieve it than Hazel. In fact, 84% of “similar”

students to Taylor will achieve grade 5 and above, whereas for Hazel the likelihood

is 51%. Is it fair, therefore, to assign both with the same target grade. For

me, this raises an important question of what data looks like at the human end.

On a whole school level, it might be useful for a school to look at what might

be the expected outcomes for their cohorts of students. On an individual level,

however, the designation of a target grade to a student has implications for that

person’s motivation, engagement and wellbeing. Certainly, the FFTD system

assumes a linear progression from the age of 11 to 16 which is very far from the

reality for a large number of young people.

At the same time, the generation

of a single grade based on performance in literacy and numeracy at the age of

11 isn’t necessarily as strong indicator of performance in the varied subject

offer studied by most 15-16 year olds. Is Hazel as likely to gain a grade 5 in Science

as she is in Art, Music or Geography?

And finally, it would be

interesting to explore the extent to which the tool developed by the Fischer

Family Trust helps the organisation to succeed in its core mission: ‘to help

children achieve their very best’ (fft.org.uk, 2017). This data tool has a fairly

limited view of what ‘their very best’ looks like: progress in academic

attainment. With the greater focus on curriculum content that is the result of

the 2019 School Inspection Framework, there is perhaps new demand for school

data systems that do more than a comparison between the attainment of similar

students.

https://fft.org.uk/about-fft/ (Date

Accessed: 31.10.22)

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-inspection-handbook-eif/school-inspection-handbook

(Date Accessed: 31.10.22)

Gordon, Harold W. & Kravetz, Shlomo,

‘The influence of gender, handedness, and performance level on specialized

cognitive functioning’, Brain and Cognition, Volume 15, Issue 1, 1991, Pages

37-61.

Comments

Post a Comment